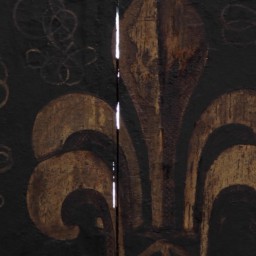

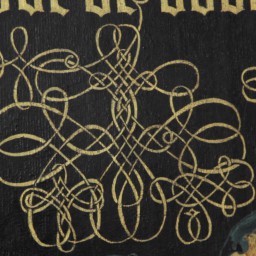

The purpose of this mobile website is to increase awareness of the history and historic value of the Cultural Heritage, the Coats of Arms of the Order of the Golden Fleece.

The website was created for use in combination with a tour of the exhibition of the Coats of Arms at the Grote Kerk, but can also be viewed elsewhere.

This production was made possible with the support of:

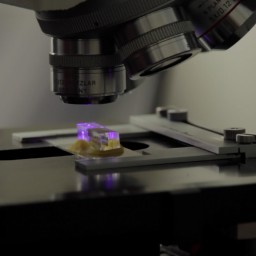

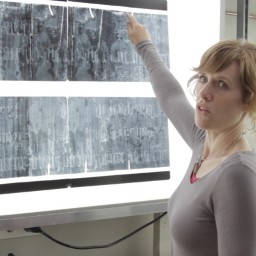

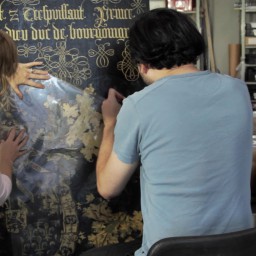

Gwendoline R. Fife – Stichting Restauratie Atelier Limburg (SRAL), Maastricht

Ed van der Vlist – National Library of the Netherlands in The Hague

Lex van Tilborg – Historical Museum of The Hague

Wendy Louw – The Hague Municipal Archives

Accountability for visuals:

National Library of the Netherlands in The Hague

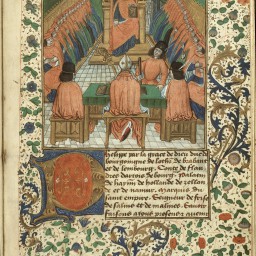

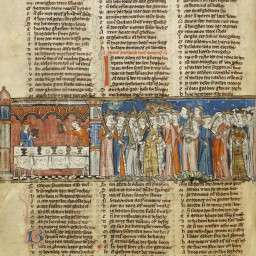

>> hs.76 E 10, Statutes, ordinances and armorial of the Order of the Golden Fleece (Southern Netherlands, 1473):portraits of the Golden Fleece knights – hs.76 E 12 – miniature of a meeting of the Order of the Golden Fleece – hs.76 E 14; historicized initial showing the coat of arms of Philip of Burgundy. – hs. 76 F 2 – Book of Hours of Philip of Burgundy (Oudenaarde, app. 1455), miniature of Duke Philip of Burgundy praying – hs. 76 F 4; Armorial of the Order of the Golden Fleece (Southern Netherlands, app. 1561):fol. 2v – portrait of Philip the Good

Historical Museum of The Hague

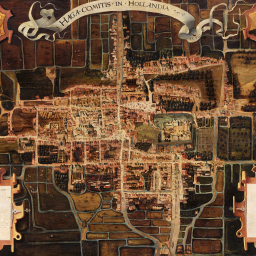

>> HGA z.g.r. 411a; Draining mill on the Hague barge canal, detail from the map of N. de Clerck and J. van Londerseel -1614 – cat. no. 52; The oldest dated urban view of The Hague, 1553. – cat. no. 21; Copy of a city map from 1570 imitated by Cornelis Elands. – cat. no. 62; Painted city plan 1658 The Hague, Raamstraat district, app. 1570 – cat. no. 53; detail from anonymous painting from 1550-1565; Square in The Hague with shops – inv. no. 54; Painting of the Hague Court Pond, Anonymous, 1567. Supplemented by various portraits of the Counts of Holland.

The Hague Municipal Archives

Hs 36,1, fol.120v-121r.; Plan of the Great Church or St. James Church from app. 1540, showing the situation before the fire in 1539

National Archives

3285b – City palace of the Lords of Egmond, on the corner of Lange Voorhout and Kneuterdijk – inv. No. 2149-11f.1r.; Opening page to the Remissorium Philippi (app. 1450), author of the book presenting it to his client Philip the Good.

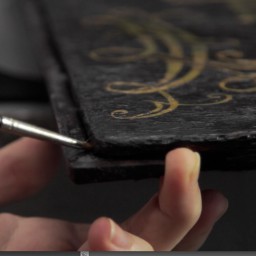

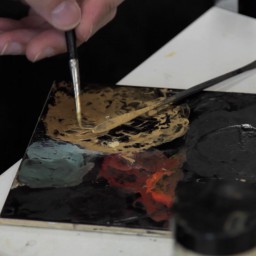

Photography Coats of Arms after restoration

Joop van Reeken Fotografie

www.reeken.com

Tips for improvement? Or missing something!

The Grote Kerk in The Hague is responsible for the content of the websites at www.1456.nl and will endeavour to keep those websites up to date and the information correct. Still, this website may contain inaccuracies or important information may be missing. The editors welcome your tips at info@grotekerkdenhaag.nl.

Copyright:

When composing this website, the makers tried to trace all the right owners. Those who, nevertheless, feel that they can assert rights are requested to contact us to make arrangements.

Nothing shown of written on this website may be reproduced or published in any way whatsoever without the prior written consent of the authors/right owners. This provision will apply to text and music (excerpts) posted and to graphic, photo and video content on this website.

Should you wish to copy or republish information from this website, please contact us at info@grotekerkdenhaag.nl.

Data consumption:

The Grote Kerk in The Hague notes that the website uses video and audio excerpts. When using a mobile data connection through a mobile network, this may cause a higher than normal data consumption. Your telecom provider may charge you additional costs, depending on your agreement with the telecom provider.

Guest WiFi:

For your interactive tour on of the Coats of Arms on site a complimentary free WiFi connection of the Grote Kerk in available.

This website has primarily been created for use with smart phones and tablets and is optimized for most versions of Android and Apple tablets and smart phones.

WiFi Disclaimer:

The Grote Kerk in The Hague reserves the right at any time to deactivate the public WiFi network for maintenance purposes. In no event can the Grote Kerk be held liable for non-proper performance of the network. Furthermore, the Grote Kerk in The Hague reserves the right to keep logs and to remove users from the network who do not observe the prevailing guidelines and/or standards of decency.

The Grote Kerk in The Hague waives any responsibility for the safety of equipment, computer configurations, removal of security or changes to files as a result of the use of the wireless network in or around the church. The Grote Kerk in The Hague waives any responsibility for changes made to the settings of your computer and cannot warrant the performance of the network in combination with your computer.